It's now November 1943...

Corfu is under German Occupation, following occupation by Italian forces.

It's almost three years to the day since Gerald and his crew crashed into the shallows of the Ionian Sea at Lefkimmi, when another plane, with a crew of ten crashes just half a mile from where Gerald's Blenheim crash-landed.

Papa Spiro and Kostas tell me that the crew of the USAF B17 'Flying Fortress' Bomber all survived and were taken into Lefkimmi and secreted away from the Germans, who were combing the island looking for the survivors from the stricken aircraft. The very courageous locals risked their own lives to do this. Many had already suffered at the hands of the Germans on Corfu but yet they gave the crewmen civilian clothing, fed and watered them... then under the cover of darkness, just as they had with Gerald and his crew they spirited the ten men away from the island and back into the hands of the allies across the Mediterranean.

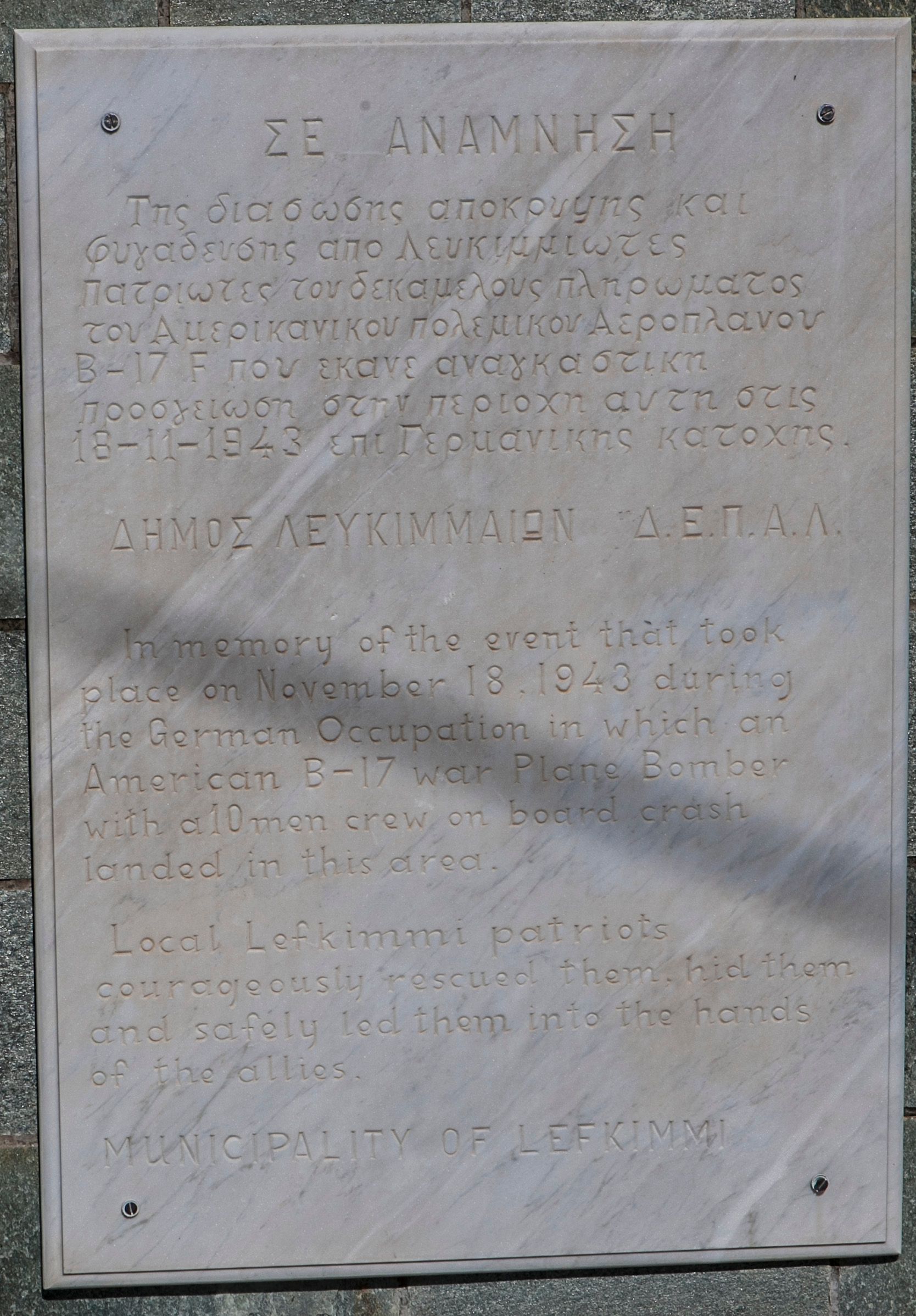

The monument...

... is situated on a similar route from Lefkimmi town that you'd go on to get to where I discovered Gerald's plane crash-landed. Once again, it's down that a pot-holed and stone ridden track leading to a crossroads where locals now take their recycling stuff to be placed into large wheelie receptacles at the side of the road. Unfortunately, 'the bins' are constantly overflowing, so the place is a sort of litter magnet, with all sorts of rubbish blowing around in the sea breeze. However, on the day I was at the monument, the beautiful Corfu sunshine highlighted the granite and white-marble of the monument which stands as a beacon and great tribute to the USAF airmen and the people of Corfu.

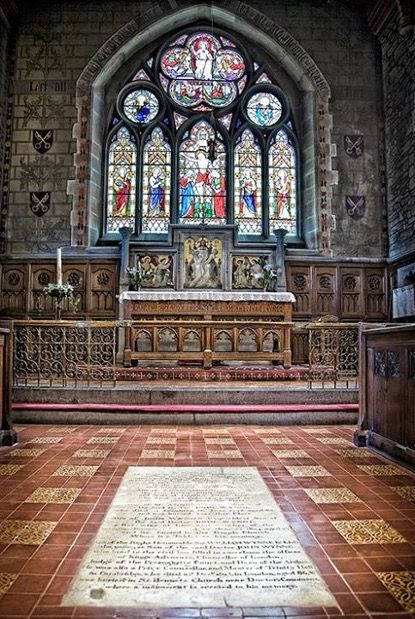

Through Kostas, I found out that Papa Spiro had on several occasions met a number of these brave American airmen who returned to Corfu after the war to thank the people of the island for their kindness and generosity. The museum behind the Church of St. Procopius at Kavos contains many artefacts from the B17 Bomber plus several letter of gratitude and photographs of the airmen who came.

We have no idea today what it must have been like to have been under the occupation of a foreign power and to take actions which might result in imminent arrest and even death.

It was a Thursday morning, the 18th November 1943 when the B17 Flying Fortress came to grief at Lefkimmi in Corfu. the crew, on their 32nd bombing mission, had just delivered twelve 500-pound bombs on the now German-occupied Eleusis Airfield, near Athens. By coincidence this is where Gerald and 211 Squadron had been based when they first arrived in Greece in November of 1940. There’s a full description of this in ‘Gerald's War.’

The routine mission was to go pear-shaped when the B17 was hit by flak, causing two of the engines of the bomber to be out of action through fire and damage. The crew were heading for Brindisi in Italy and as the plane headed back west, another engine failed, leaving the crippled bomber flying on just one engine over the Ionian Sea. Luckily for the crew, as was the case for my uncle, Corfu could be seen below, and the pilot Captain Dick Flournoy headed for the island as best he could.

The crew prepared for the worst as the plane went down near the shoreline at Lefkimmi, but the experienced pilot Dick Flournoy managed to pancake the plane down on the salt-flats and the ten-crew survived. The first thing the crew did was, as procedure dictated (both for allies and the Germans), to attempt to destroy the plane, to ensure no equipment and nothing sensitive fell into the hands of the Germans.

As with Gerald's crash landing, locals were on the scene within minutes to help the crew escape. The crew were warned that Germans would soon be swarming all over the area and the crew quickly abandoned their efforts to destroy the plane. As forecast, the Germans arrived on the scene within fifteen minutes but were unable to find any of the plane’s crew. They were thwarted by the Lefkimmi Corfiots who, within this time had given the crew civilian clothing and had led them away to safety within minutes, so no US airman was captured.

Captain Dick Flournoy was led to a tool shed in an olive grove by a child and spent the next two days in hiding there. Gunner Fred Glor was taken to a nearby field by a young woman who had been hoeing there and hid for the next night in a nearby shepherd's hut. The remainder of the ten-man crew were similarly hid away. All the Germans saw when they arrived were locals busy stripping the plane.

Co-Pilot, Joe Cotton arrived in Lefkimmi town before the others on the actual afternoon of the crash and pretended to work pressing olives with mules as two Germans arrived at the land searching for survivors. The Germans saw Cotton but ignored him completely, so his luck evading capture held out. He then spent his first night hidden away in a church with four other crew members. These fortunate crewmen were then housed with a Corfiot called Harry Pappas who had lived in the USA before the war. Unknown to the men Harry Pappas was leader of the local resistance at the time.

Other crew were hidden by Corfiots in a variety of places, all at great risk to themselves. Crewman Gunner Fred Glor had the best accommodation, being housed in Lefkimmi's only hotel at the time. Bombardier Ernie Skorheim's stayed with wheelwright Josephus Montezago at his home.

When questioned by the Germans, the locals claimed the 'five-man' crew had run away from the scene, stealing a boat in the process, and heading out to sea. Added to this, the Germans were later told, in a 'bogus report,' that the airmen had been spotted in the north of Corfu where they then concentrated their search. This meant that the airmen could, in the short term, be kept safely in Lefkimmi without fear that the Germans would return to search for them, well at least in the short term

Food rations for all were slim, you will recall in a previous blog, Kostas saying that the Germans stole nearly all the locals' food and so locals were starving even before the arrival of the airmen but all the same took it upon themselves to feed the crew and keep them safe. Bombardier Ernie Skorheim said that he was fed by Josephus' wife Tina with an ample diet of bean soup and coarse wheat-and-corn bread dipped in olive oil. Added to this, the people of Lefkimmi (and so too the crewmen) were able to survive more adequately than other Corfiot folk, as their proximity to the sea meant they also had a diet of fresh fish, caught in the waters surrounding the island.

Some crewmen, including Skorheim caught malaria from the mosquito bites suffered whilst sleeping rough in the marshes on the first night. Skorheim learned that Josephus Montezago's son had died of malaria, so considered himself fortunate not to have succumb too seriously to the illness himself. This was probably due to the fact that a local pharmacist was able to give him quinine to stave off many of the worst symptoms of the disease. The pharmacist assisted others too; they were also treated with leeches over the next month or so whilst they were on Corfu and in hiding. All recovered well during this time, but they were still not out of danger as the Germans carried out constant searches of the area and its population.

Worse was to come for the airmen, with the arrest of Captain Dick Flournoy's Corfiot host by the Germans for 'smuggling' on 18th December 1943. On being questioned, he blurted out, no doubt to save himself from too harsh questioning or a worse punishment, that the airmen were still hiding in plain sight in the area. Luckily, the interpreter at the interview was a member of the resistance and gave advanced notice to the airmen and their hosts that they should flee to the hills above Lefkimmi to avoid capture. So it was that, on 19th December 1943, the Germans surrounded Lefkimmi and conducted house to house searches, but they found nothing. Thanks to the interpreter, the Americans had vanished.

The one added benefit to the 'smuggling incident' prior to Christmas 1943 was that all the crew of the B17 were together again for the first time since the crash landing, although this time, they were all residents of a lowly hut in the hills. The crew foraged for food, ensuring they kept out of sight of German patrols, but once again were supported in their survival efforts by Corfiots who brought them a share of the little food they had for themselves. The crew even celebrated Christmas, risking a lit fire on which they roasted onions and fish. Together with olives, tangerines, and olive oil saturated bread, they kept reasonably satiated.

On 31st December 1943 the crew were informed by Corfiot resistance members that they should prepare to move out, the plan being to get them to the northern half of Corfu, where, in places there were only two miles between the island and the mainland of Albania. This operation would be fraught with difficulty as the Germans had an airbase and encampment full of troops on the roads between and of course, there was Corfu Town in the middle which would not be an easy place to get through without being spotted.

So, New Year's Day of 1944 became a day of emotional goodbyes between the crew and their Corfiot hosts. The ten crew began their hazardous journey well before dawn in donkey carts loaded with olive oil. The crew, who had been told to keep quiet for fear of being found out, set off in twos at set intervals in five oil carts, all posing as Greek workers. The roads heading towards Corfu Town were poorly made up and hilly along the coast, so progress was very slow, especially when one of the carts was stopped by Germans who were clearing a fallen tree from the road. A close call, but on this occasion the Germans didn't speak to the men. There was another incident that could have been a near-miss too, as Co-Pilot Joe Cotton, fell asleep on his cart and his service revolver was exposed for some time until he was told to cover it up before it was noticed by the enemy.

As the afternoon of a cold and yet sunny 1st January began, the olive-oil wagons had reached the outskirts of Corfu Town, but there they had to stop and from then onwards they had to set out on foot, once again in small groups with their accompanying Corfiot minders. At this point of their journey, the fleeing Americans had no option but to pass right through the middle of the German army base at Corfu Town which straddled the road on either side. Pilot, Captain Dick Flournoy, was a very tall fellow and was worried that his grand height of 6'4" looked properly out of place amongst smaller statured men, but luckily, because it was the very first day of the year there were many others out strolling, including on and off-duty Germans just enjoying the sunshine, so all had to use their best recently acquired Greek for hello (Γειά σου) and good-afternoon (καλό απόγευμα)!

Once they had passed by the German troop encampment, they came to the German airbase where B17 Co-Pilot, Joe Cotton, seeing several planes to the side of the runway, in the manner of Indiana Jones, thought about stealing one of them until talked out of it.

With Corfu Town and many Germans now behind them, they walked on towards their goal, the village of Kontokali, about another four miles on. German trucks carrying supplies and troops would pass by on the roads but a well-rehearsed shout from the Corfiot resistance accompanying them would see them all jump into the ditches and undergrowth so as not to be detected.

Night had fallen before they reached Kontokali and all were completely exhausted. The crew were shown to a large three-floored house on the outskirts of the village and once again their hosts treated them well, serving them with a meal of chickpea soup, spaghetti and bread dipped in copious amounts of olive oil. All washed down with plenty of wine to help them forget the ordeal they were going through. New Year's Eve night and into 2nd January 1943 was a stormy night but all slept well, ably assisted by the wine.

The crew had a chance to rest on the second day as they were told the next leg of their journey would not begin until darkness had fallen. This is when they were taken to a deserted beach on the Ionian coastline. Such were the dangers of the time that all of the crew were piggybacked across the beach by locals to two waiting fishing boats, which avoided them leaving footprints for German patrols to find.

Crossing the short distance to Albania was not easy either, as the whole area was now under German control, and this included the waters of the Ionian Sea which were regularly patrolled by the German naval vessels. All would be shot if caught! The Corfiot fishermen rowed on tirelessly through the night for twelve or more hours, and by first light they had the shores of Albania in front of them. As they landed on unfamiliar shores once again, the Kontokali fishermen bade their farewells, placing the American crew into the hands of the Greek mainland resistance, with whom they remained for almost three months, so their ordeal was far from over.

An amusing incident surrounding their time with the Greek resistance was recounted by Pilot Captain Dick Flournoy and Gunner Fred Glor. They were talking about how their life might be after the war with a local shepherd. They chatted about their intention to make lots of money whereupon the shepherd headed off into the snow, returning shortly afterwards with a local young woman in uniform. The woman brought with her a bottle of ouzo, and she started being all amorous around the two airmen. Dick Flournoy and Fred Glor, puzzled at the behaviour, asked what was going on, only to have it explained to them that the word money in English sounded like the Greek word for prostitute.... so, the shepherd had been doing his best to accommodate what he thought was their needs!

The months passed and the crew of the B17 were walked from resistance camp to resistance camp to avoid the Germans who occupied the whole of Greece at this time. The airmen were poorly dressed for the Greek winter, and several became sick or lame. Contact, with a view to evacuating the crew back to their home base, fell through time after time which resulted in the crew spending more time in deteriorating conditions in Greece. With great relief, on 15th March 1943, together with the seven-man crew of a British Lancaster bomber who had been with them since mid-January, the B17 crew were placed aboard an Italian submarine motor launch which was there to deliver supplies to the Greek resistance.

The motor-launch arrived in Italy on the morning of Tuesday 16th March and the B17 crew were taken to the American base at Bari in an army truck. To a man, the crew revered the exploits of the Corfiots and Greeks who had helped them survive.

Quote: 'They were ready to do whatever was needed to see to it that we survived.'

As you have seen from the museum at the rear of St. Procopius Church in Kavos, several of the crew have kept in touch with the people of Corfu and many of the crew members have visited and revisited Corfu, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s. They met and were photographed with Lefkimmi people who helped them. As an example, Gunner Fred Glor came back to Lefkimmi for the first time in 1988 and visited the scene of the crash of his B17 Flying Fortress. Astonishingly, there he saw a woman hoeing the ground and tending to her allotment. When he went over to talk with her, with his interpreter, he found out that she was the same woman who, forty-five years earlier, had been hoeing the same field and had helped him escape.

Lest We Forget!

The plight of the crewmen of the B17 is described in the book:

Aircraft Down! Evading capture in WWII Europe

by Philip D. Caine.

ISBN 1-57488-234-1

#Lefkimmi #corfu #GeraldsWar #EmotionalJourney #WarTale #HistoricalNovel #HiddenTruths #WartimeSaga #USAF